¿A favor de la nacionalización? – Parte I – Willi Noack – 16.6.2005

¿A favor de la nacionalización?

Willi Noack

He agregado los signos de interrogación al título de una nota de prensa publicada en EL DEBER el domingo pasado sobre la “Crisis. Un estudio revela que la mayoría quiere que se recupere la administración de sus hidrocarburos”.¿Qué mayoría?

El resultado en base a 850 encuestados ha sido: un 76% aprueba la nacionalización, un 21% no aprueba y un 3% no sabe o no responde. Fueron entrevistados “Ciudadanos mayores de edad en viviendas particulares de las ciudades de Santa Cruz (250) La Paz (200) Cochabamba (200) y El Alto (200).” El error máximo es del 3,4%.

A ver si interpreto acertadamente los resultados.

Solamente una ínfima minoría del 3% admite que no sabe o no desea contestar. El 76% en cambio sabe supuestamente lo que significa la nacionalización de los hidrocarburos pues la aboga. Está supuestamente consciente de las consecuencias. Sabe de las reacciones probables (y ya anunciadas) de los inversionistas. Este 76% supone, supuestamente con realismo y pragmatismo, que Bolivia precisa enormes cantidades de capital para la exploración y explotación de los yacimientos (en 4.000 o más metros por debajo del suelo) y “know-how” de la última generación, y supuestamente confía en que el país, cuyo riesgo está calificado en “negativo”, va a conseguirlo.

Este 76% tiene –¡seguro está!- recuerdos de la baja eficiencia y de la alta corrupción de la ex-empresa estatal YPBF. La empresa estatal a refundarse (¿y luego nuevamente refundirse?) va a administrar los hidrocarburos e implícitamente el 76% supone que lo va a hacer idóneamente. ¿Se trata de una suposición realista? ¿Habrá –como se estila hacer- nepotismo y prebendalismo en cuanto a la contratación del personal jerárquico? ¿Habrá respeto por los méritos en la selección de los empleados o el señor Solares colocará un sindicalista de su agrado a la cabeza como era el Sr. Nelson Bustos durante la UDP?¿Habrá corrupción?

“El analista energético Carlos Alberto López dice que se habla muy liviana e irresponsablemente de este tema.”, citando EL DEBER. Los radicales lo han declarado “enemigo de BOLIVIA”. El columnista Gustavo Maldonado recientemente nos ha orientado sobre las normas legales vigentes en el caso de la nacionalización.

Para formarse una opinión propia sobre este tema tan complejo y complicado, de muchas repercusiones directas y –quizás sobre todo- indirectas, no basta pensar con sentimentalismo nacional (evocando la soberanía restringida por la dependencia de la ayuda internacional). Por supuesto que se debe negociar para conseguir beneficios para el país lo que está al alcance bajo enfoque realista de la factibilidad. No sirve dejarse guiar por anhelos que son inviables (“wishful thinking”). Invito leer una reflexión relevante, publicada el 16 de octubre de 2003.

Es muy importante que una gran mayoría de la población entienda el tema y no se junte a una corriente de opinión creada hábilmente por grupos radicales que buscan la convulsión del país – lo que en este “junio funesto” (Mario Rueda Peña) casi lograron. Cuando uno ENTIENDE la absoluta necesidad de disponer de inmensos montones de capital de riesgo y disponer de la alta tecnología para explotar racionalmente EN BENEFICIO DE BOLIVIA este recurso, es obvio que no debemos nacionalizar los hidrocarburos. Es más. Si pretendemos, además, INDUSTRIALIZAR la materia prima o convertir el gas en diesel (una planta grande requiere miles de millones de dólares), necesitamos un país que inspira al inversionista CONFIANZA mediante una seguridad jurídica que en este momento no existe. Consecuencia: paralización de nuevos proyectos.

Intento hacer un alegato ojalá convencedor para que muchos del 76% revisen su preferencia. Claro que los adoctrinados o buscadores de beneficios personales o grupales a favor de la nacionalización van a insistir en su dogma – pues poco o nada están interesados en el futuro mejor del país.

Estaba buscando datos fidedignos sobre el total de pagos al Estado, sea en forma de regalías o impuestos, en diferentes países. Esta comparación representa una información importante de referencia. Hasta finalizar esta redacción lamentablemente no la he conseguido. Lo que escuché de gente experta es que un 50% de regalías sería una cuota razonable, aceptable para las empresas y dejándoles una ganancia del orden del 20%. 50% de un valor (“precio en boca de pozo”) que se orienta por el valor de hidrocarburos en el mercado bajo criterio de la demanda y oferta, y considerando las subas y bajas del precio.

¿Cuál sería una solución probablemente viable y factible y que otorgue al país el beneficio óptimo a largo plazo (y no el máximo a corto plazo)? ¡Con toda seguridad no la nacionalización! Lo óptimo sería recibir el 50% en forma de regalías (y no exigir el pago de impuestos adicionales) sobre un valor real y, además, garantizar que el país siga explotando su riqueza hidrocarburífera con visión de futuro, léase: satisfacer una demanda en crecimiento inimaginable. ¡Seamos realistas! ¡No más litio!

(Este artículo será publicado, en una versión más corta por el espacio restringido disponible en el periódico EL DEBER en fecha 19.6.2005, sin los anexos a continuación. WN)

Una opinión en pro de la nacionalización cuestionando el nuevo Ministro:

15-06-2005: La nacionalización de los hidrocarburos y la política “gas por mar” no convencen a nuevo gobierno

________________________________________________________

Relacionado (por razones de espacio no publicado en EL DEBER):

LA UTOPIA DE LAS NACIONALIZACIONES

I. REALIDADES DEL MUNDO ACTUAL

No existe nacionalización de gas: No hay precedentes para la nacionalización de reservas de gas.

Mundo globalizado, nos guste o no: Resulta muy difícil pensar que luego de expropiarles sus reservas alguna empresa privada de porte importante quiera comprarnos gas.

En contra flecha con las tendencias: en todo el mundo el estado más bien está retirando su participación económica activa en el sector

II. EL DESAFIO DE LOS MERCADOS

Mercados son los que faltan: En general, en el gas a nivel mundial, lo que faltan son mercados, no reservas

Mercados extremadamente difíciles de desarrollar: Ideas y conceptos para mercados hay muchos, pero concretarlos y mantenerlos, son contados.

El gas se vende de acuerdo a normas y reglas de mercados internacionales

III. LOS DESAFIOS ECONOMICOS Y FINANCIEROS

Financiamiento – “¿de dónde va a venir la plata?”: La tendencia es que los gobiernos e instituciones multilaterales dejen de prestar capital donde el sector privado puede hacerlo, y están más abocados a proyectos de índole social.

Costo económico / de oportunidad para el país: Con una nacionalización, volveríamos al dilema: si invertir en el sector o en el financiamiento del déficit

Las nacionalizaciones siempre se pagan. Siempre se han pagado.

IV. LOS DESAFIOS TECNOLOGICOS

Atraso: Con nuestra precaria situación financiera y extrema pobreza, tiempo es lo que no podemos perder.

El desafío de transformar nuestras reservas en dinero depende de tecnologías que no controlamos y para las cuales necesitamos aliados estratégicos

V. LA IMPORTANCIA DE LA LEGALIDAD

Es impensable en el mundo moderno no cumplir contratos internacionales. Los vacíos jurídicos que existían en el Siglo pasado ya fueron cubiertos por nuevas formas jurídicas y acuerdos que, en mucho caso, son de país a país y no solo de empresa a empresa.

Además la legalidad es la principal y quizás única defensa de los Estados débiles

.

VI. EL FALSO DILEMA DE LA PROPIEDAD

El concepto antiguo de nacionalización era para que el partido controlado por los trabajadores asumiera en nombre de estos, la propiedad de los medios de producción. En Bolivia sabemos lo que ha pasado cuando los partidos han asumido el “control” de una empresa pública. Esto nunca ha significado una propiedad nacional real, sino más bien una apropiación de parte de castas que fomentaron la corrupción.

VII. LOS ASPECTOS IDEOLOGICOS

En realidad la supuesta nacionalización no es más que una cortina de gas para encubrir una ideología que pretende tomar el control de otros medios de producción más controlables por sectores sociales: tales como la tierra, las fábricas, la banca y otros instrumentos de la producción que ya es nacional, que sostiene al país, pero que también sabe mirar hacia fuera y hacia el futuro.

VII. CREDIBILIDAD Y DIGNIDAD

Credibilidad del país: Además, perdemos credibilidad y confiabilidad no solo con las empresas que están en Bolivia, sino también con otras

Moral e Imagen: Se trajeron las grandes inversiones de afuera bajo ciertas condiciones, y ahora, cuando han dado sus frutos, y cuando nos conviene, cambiamos las reglas a nuestro favor.

En resumen, el concepto de nacionalización, puede sonar atractivo, pero es otra la situación cuando se lo analiza en el marco de las realidades.

INFORMACIÓN para entendidos del tema (fuente: JP Morgan):

Bolivia tax changes have little earnings impact but could curtail growth

Bolivia edging closer to hiking upstream taxes to 50%. The threat of a hike in Bolivian production taxes – effectively royalties – from 18% to 50% is looking increasingly real. Following months of controversy and civil unrest, the tax bill has made its way from the lower house of congress to the senate, with the legislature so far rejecting President Mesa’s proposals to make the increase in production taxes deductible against other taxes.

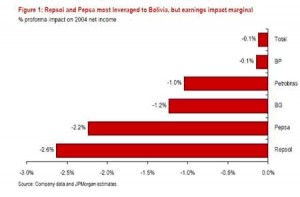

Limited earnings impact of less than 3%… While we would hesitate to predict the final shape and form of the new upstream tax regime, we conclude that even under the present proposals the earnings impact for our coverage universe would be limited. Repsol appears most exposed, on our estimates, with 2.6% downside to earnings, followed by Petrobras Energia with a 2.2% earnings exposure. Other important operators, such as Petrobras and BG, face around a 1% downside to earnings on our estimates (see chart opposite).

…but economics of future growth could be destroyed. While the earnings exposure may be modest, we believe any hike in Bolivian upstream taxes could have material negative implications for growth prospects for Bolivian gas, which represents the southern cone’s largest resource of natural gas. Economics already look stretched and, under our estimates, a tax hike of this magnitude could see post-tax returns drop from 12% to 8% if the additional royalty is income tax deductible and further into negative territory if no deductibility is allowed – making the case for future investment difficult to justify. Given Brazil’s – and increasingly Argentina’s – reliance on Bolivian gas to cover domestic gas deficits, such an outcome could have wider ramifications for gas prices (upward pressure) and security of supply in the southern cone (potential shortfalls).

Table of Contents

Bolivia royalty rate could rise to 50%……………………………….3

Little EPS impact but future growth at risk ……………………….3

Latin American Oils…………………………………………………………4

Greater earnings impact for Pepsa (UW), but Petrobras (OW) looks more exposed in

the long-term……………………………………………………………………………………….4

European Oils: Repsol most exposed………………………………6

Repsol (UW)………………………………………………………………………………………6

Total (OW)…………………………………………………………………………………6

BG (OW) ……………………………………………………………………………………………….6

BP (N)…………………………………………………………………………………………7

Bolivia‘s energy sector in context ……………………………………7

Vast gas resources but serious socioeconomic challenges…………………………………….7

Bolivia gas reserves second highest in LatAm ……………………………………………………7

Appendix: Profitability impact of increased royalty rate ….12

Bolivia royalty rate could rise to 50%

Legislation currently being debated in the Bolivian congress could raise royalty rates on oil and gas production to 50% from the current 18%. The proposed legislation calls for the introduction of a 32% “production tax” (effectively a royalty, in our view) in addition to the current 18% royalty charged to oil and gas companies. This tax would apply to both existing and future upstream projects in Bolivia, effectively

making the production tax retroactive.

The lower house passed the measure on March 10, and the upper house began debating the bill last week and could vote by the end of April. Even if the upper house were to approve the new 32% production tax, implementation could be several months away as details must be ironed out on the broader hydrocarbons bill, of which the royalty hike would be only one of 142 items. Furthermore, the president has veto power, which he could be inclined to exercise as the legislature has introduced modifications to the original bill with which he has said he does not agree. one key point is that the proposed royalty increase making its way through congress would not be eligible for income tax deductibility, in contrast to President Carlos Mesa’s original proposal.

Little EPS impact but future growth at risk

While we would hesitate to predict the final shape and form of the new upstream tax regime, we conclude that even under the present proposals the earnings impact for our coverage universe would be limited. Repsol appears most exposed, on our estimates, with 2.6% downside to earnings, followed by Petrobras Energia (Pepsa) with a 2.2% earnings exposure. Other important operators, such as Petrobras and BG, face around a 1% downside to earnings on our estimates (see Figure 1).

Material negative implications for future growth possible

While the earnings exposure may be modest, any hike in Bolivian upstream taxes could have material negative implications for growth prospects for Bolivian gas, which represents the southern cone’s largest resource of natural gas. Economics in Bolivia’s upstream sector look stretched. Under the current fiscal regime we estimate that the Repsol-YPF operated Margarita field will achieve a posttax rate of return of 12.2% (see Table 2 in the appendix on page 12). However, should a 50% royalty be introduced – while allowing income tax deductibility – this return would drop to just 8.4% (see Table 3 in the appendix on page 12) under our estimates, making the case for future investment difficult to justify. Indeed, if no income tax deductibility were permitted, we believe returns would turn negative. We would therefore anticipate that a tax hike would lead foreign operators to shelve development plans and abandon export projects.

Clearly, this would have a negative impact on future production growth thus limiting the scope for companies to book a greater share of the substantial technical gas reserves in Bolivia. Given Brazil’s – and increasingly Argentina’s – reliance on Bolivian gas to cover domestic gas deficits, such an outcome could have wider ramifications for gas prices (upward pressure) and security of supply in the southern cone (potential shortfalls).

Latin American Oils

Greater earnings impact for Pepsa (UW), but Petrobras

(OW) looks more exposed in the long-term

If the additional 32% production tax legislation were to be approved and enacted, we estimate that the impact on Petrobras and Petrobras Energia (Pepsa) would belimited. We estimate that Petrobras’s pro forma net income would fall by 1.0% and Pepsa’s by 2.2% on the back of the decreased net revenue from Bolivian oil and gas production (before any one-off impairment charges that could potentially arise).

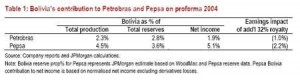

Bolivia represented 2.3% of total production at 45.5kboepd and 2.8% of total reserves at 335mmboe for Petrobras in 2004 (see Table 1 below). Bolivia’s proportional contribution is larger for Pepsa, accounting for 4.5% of the Argentine company’s total production at 7.6kboepd and 3.6% of total reserves, on our estimates

(see Table 1 below).

More radical outcome implies graver risks for Petrobras

Under a worst-case scenario of Bolivian revolution or hydrocarbon industry nationalisation (however likely), Petrobras would face much more serious concerns involving security of supply issues for gas imports, as well as downstream exposure, in our view.

Brazil relies on Bolivia for one-third of gas consumption needs

In 2004, Petrobras’s natural gas imports from Bolivia accounted for just over one-third,or 19.4mcm/d, of Brazil’s total natural gas consumption, leaving Brazil vulnerable toserious supply shortfalls were Bolivian gas flow to be interrupted. While this appears an unlikely (and irrational) outcome, in our view, limitations to future growth in Bolivian gas supply could also represent a constraint given Brazil’s express desire to further boost natural gas’s share of the country’s primary energy mix.

Interestingly, in what we believe may perhaps be reflective of security of supply concerns, Petrobras and the Brazilian government have appeared more focused on domestic, Brazilian natural gas development in recent months. For its part, Petrobras has highlighted its promising 400bcm Mexilhao discovery in the Santos Basin for which the company is discussing a potential development partnership with RepsolYPF. Moreover, the government has increased the gas-prone acreage for its upcoming seventh offshore licensing round. However, while these represent first steps, no Santos Basin projects have yet been sanctioned, leaving open the question

of near-term solutions were a worst-case scenario to develop in Bolivia.

Bolivian refining capacity minor in overall scheme of things

While Petrobras also carries exposure to Bolivia in the downstream segment that could be affected were a more radical outcome to take place in Bolivia, the impact would be relatively minor in the context of the company’s overall position, in our view. Petrobras has a 51% stake in Empresa Boliviana de Refinación (EBR) which owns two refineries in Bolivia and nearly 100 service stations. Its total Bolivian refining capacity of 48kbpd represents under 5% of Petrobras’s total. Pepsa is Petrobras’s minority partner in EBR, holding a 49% stake in the company. The equity-accounted contribution from EBR for Pepsa represented no more than $6.1m or 3% of total net income in 2004.

Petrobras official line: no comment until final decision

Petrobras appears to be taking a wait-and-see attitude, with CFO José Sérgio Gabrielli on the record in press reports as saying that no decisions regarding Bolivia will be made until legislation has been finalised. Brazilian Energy & Mines Minister, Dilma Rousseff, has stated that she considers the proposed legislation as “prohibitive” to investment. According to press reports, RepsolYPF has cancelled its plan to build a 20mcm/d pipeline to transport gas to Argentina from Bolivia ($1bn estimated capex/ 2007 start-up date) and has said it might also abandon some gas fields and reconsider future gas investments if the senate approves the law.

Stock impact: none for now

Though potentially negative, neither Petrobras nor Pepsa would be adversely affected in a material way were Bolivian royalties to be raised to 50% from the current 18%, in our view. Under a worst-case scenario involving re-nationalisation of the hydrocarbon industry or a popular revolution, Petrobras could face more serious consequences while Pepsa, in contrast, would escape relatively unscathed, in our view.

European Oils: Repsol most exposed Repsol (UW)

Largest gas reserves in Bolivia

Repsol gained the vast majority of its asset base in Bolivia following its acquisition of Argentina’s YPF. The former Argentinean state oil company had formed a 50:50 joint venture (Andina) following the ‘capitalisation’ of Bolivia’s petroleum industry in the late 1990s. The company now holds the largest gas reserve position in Bolivia, over two-thirds of which remains uncommercialised.

Modest earnings impact but major strategic blow

Whilst we estimate that the net effect on Repsol’s earnings at the group level would be modest at 2.6%, strategically it would represent a major blow to the company should the new, harsher fiscal terms be pushed through by the Bolivian government. In particular, the proposed construction of a 20Mcm/d cross-border pipeline into Argentina would be unlikely to go ahead and would therefore curb the company’s ability to grow Bolivian upstream volumes beyond our current base case of 17Mcm/d (600 mmcfd) in 2008. In addition, Repsol faces pressure from both the Argentinean and Bolivian governments to continue to invest in gas projects in on both sides of the border with the aim of meeting growing demand in Argentina, leaving the company in an extremely delicate position.

Total (OW)

Itau field holds substantial reserves but no sales agreement yet

The key asset for Total is the stranded Itau gas field which, although it holds 3P reserves of 3.3 tcf (1.35 tcf net), has yet to secure a gas sales agreement. Total had been involved in a consortium which was investigating the possibility of commercialising its reserves via the construction of an LNG plant. However, these discussions were shelved in 2003 due to border disputes with its neighbour Chile upon whose coast the plant was to be constructed.

Negligible financial impact even in worst case scenario

As there is no immediate effect to earnings for Total, the overall impact of the new harsher fiscal terms would most likely form the withdrawal of the company from Bolivia. That said, Total continues to have a position in the Argentinean power and gas distribution sector, and, as such, a further increase of gas prices by the Argentinean government could offer the opportunity to leverage its existing position there in order to crystallise the value of its Bolivian gas reserves. We believe the worst case scenario, therefore, is that Total will have to take a write-down on its Bolivian asset base, although this will be negligible given its limited investment in the country to date.

BG (OW)

Itau and Margarita fields are key assets

Key assets in Bolivia for BG are the Itau (see comment on Total above) and Margarita fields. The Margarita field is currently producing some 25 mmcfd (9 mmcfd net) and, under our base case, is set to increase to 70 mmcfd by 2007. However, this is significantly below initial expectations largely as a result of weaker-than-expected Brazilian demand. Margarita’s output is currently routed through the BBPL.

Small but immaterial net negative impact

As with the other IOCs, the net negative effect on earnings is small at 1.2%, rising to 1.8% by 2008. However, since the Brazilian government is in a more comfortable position in terms of gas supply following the discovery of the giant Mexilhao gas field, BG’s ability to increase output from its Margarita field looks constrained at best. Therefore, in our opinion, under the worst case scenario the company will either withdraw completely from the country, or simply run down its assets at Margarita.

BP (N)

Through a legacy joint venture agreement following BP’s merger with ARCO, the company has assets jointly held through its 60% owned Pan American subsidiary. Given the low level of current and projected output from its Bolivian asset base, the net effect on BP’s earnings between 2004 and 2008 is between 10 and 20 basis points on our estimates. It is highly likely, therefore, in our opinion, that the company would seriously reconsider the viability of sustaining its position in the Bolivian upstream sector should harsher fiscal terms be pushed through by the Bolivian government.

Bolivia’s energy sector in context

Vast gas resources but serious socioeconomic challenges

Bolivia has wrestled with internal conflict over resource development for the past several years as an impoverished indigenous community fears and resents perceivedexploitation by foreign companies. The opposition group MAS (Movement Towards Socialism) has pushed for increased taxation of international oil and gas companies, while current president Carlos Mesa has cautioned that excessive royalties will discourage much needed foreign investment. In the wake of widespread protests and blockades, Mesa has twice offered to resign this year (Congress has rejected both his offers). His predecessor, Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozado, was forced to resign in October 2003 after dozens died in protests against exports of gas through neighbouring Chile, with whom land-locked Bolivia has had a dispute regarding coastal access dating back to the late nineteenth century.

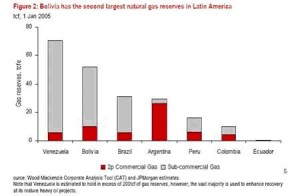

Bolivia gas reserves second highest in LatAm

Bolivia is almost entirely dependent on its substantial hydrocarbon resources, with the industry accounting for more than 90% of the GDP of Latin America’s poorest economy. Of the estimated 57 tcfe of remaining 3P reserves, over 90% is made up of natural gas, making it second only to Venezuela in terms of “gas in the ground” (see Figure 2).

fecha: 2005-07-29 14:47:12

autor: Willi Noack